“One hundred years from now, It won’t matter what car I drove, What kind of house I lived in, How much I had in my bank account, Nor what my clothes looked like, But, the world may be a little better Because I was important in the life of a child.” – Anonymous.

Dr Jinan Harith Darwish pays tribute to one of her cystic fibrosis patients.

The abrupt course of respiratory failure that led to the demise of Sukaina Hamed Fadhul on December 2, 2014, during her last admission to Salmaniya Medical Complex a fortnight after she celebrated her 14th birthday, urged me to pay tribute to her and to her two siblings who lost their lives to cystic fibrosis (CF) at the ages of 26 days and 14 years respectively. The Fadhul family became accustomed to having their children surrounded by medical paraphernalia, using bizarre-looking flutter devices and taking an array of nebulisers and medications.

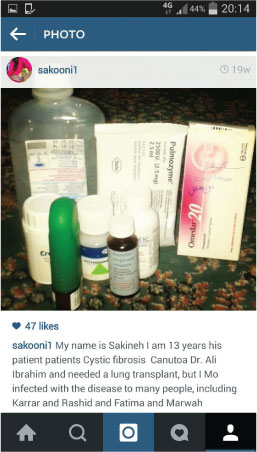

Sukaina had great hope to go abroad to Great Ormond Street Hospital in London for advanced medical care and an ultimate lung transplant, so she could grow to become a lung transplant surgeon and cure people who share her disease. One cruel twist is that CF can be a lonely and solitary condition as CFers are advised not to meet face-to-face for fear of making themselves more ill from cross-infection (different people can carry different bacteria). It means they cannot socialise easily or give each other regular support; therefore she reverted to utilising social media through her Instagram account to communicate with her CF counterparts and to search for a cure by following global medical professionals treating the disease. As much as she despised her daily health battle, it had given her a perspective on life that many people may never attain or will only encounter later in life. Sukaina, with her life-threatening condition, had a pronounced ability to not only identify but fully appreciate magic moments, as they contrasted so strikingly with her usual daily hardship. Death, as heartbreaking as it was to each person whose life she blessed, liberated her from a disease that was eating her away. On her last eve, she addressed her father with a living will that confirmed for a final time her altruism.

Sukaina had great hope to go abroad to Great Ormond Street Hospital in London for advanced medical care and an ultimate lung transplant, so she could grow to become a lung transplant surgeon and cure people who share her disease. One cruel twist is that CF can be a lonely and solitary condition as CFers are advised not to meet face-to-face for fear of making themselves more ill from cross-infection (different people can carry different bacteria). It means they cannot socialise easily or give each other regular support; therefore she reverted to utilising social media through her Instagram account to communicate with her CF counterparts and to search for a cure by following global medical professionals treating the disease. As much as she despised her daily health battle, it had given her a perspective on life that many people may never attain or will only encounter later in life. Sukaina, with her life-threatening condition, had a pronounced ability to not only identify but fully appreciate magic moments, as they contrasted so strikingly with her usual daily hardship. Death, as heartbreaking as it was to each person whose life she blessed, liberated her from a disease that was eating her away. On her last eve, she addressed her father with a living will that confirmed for a final time her altruism.

Cystic fibrosis is one of Bahrain’s not so uncommon, life-threatening recessive inherited diseases. An individual must inherit two defective CF genes, one from each parent, to have the disease. Each time two carriers conceive, there is a 25 per cent chance of passing cystic fibrosis to their children; a 50 per cent chance that the child will be a carrier of the CF gene; and a 25 per cent chance that the child will be a non-carrier.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), the incidence of CF in Bahrain is 1:5,800.This is based on a 1998 study published locally. Cystic Fibrosis affects around 56 people that we know of that follow up at Salmaniya Medical Complex, with ages ranging from 10 months to 23 years. There are others who are overwhelmed with the diagnosis and travel to their countries of origin for treatment.

In 1962, the UK predicted the median survival age was 10 years. The median predicted survival for someone with cystic fibrosis currently stands at 41 years. According to the statistics in the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation’s national patient registry, currently half of those with CF will live to over 41 years – many people even live into their fifties and sixties. A baby born in the UK today can be expected to live longer. Yet, today in Bahrain, we don’t have any statistics on the median predicted survival; but less than a handful have made it past their childhood into adolescence.

In the UK, since October 2007, all babies are offered screening for CF shortly after birth as part of the heel-prick blood test. Unfortunately, that’s not the case in Bahrain. The National Newborn Screening Programme encompasses sickle cell disease, thalassemia, G6PD reduced activity and congenital hypothyroidism only.

In the UK, since October 2007, all babies are offered screening for CF shortly after birth as part of the heel-prick blood test. Unfortunately, that’s not the case in Bahrain. The National Newborn Screening Programme encompasses sickle cell disease, thalassemia, G6PD reduced activity and congenital hypothyroidism only.

Cystic fibrosis is a chronic progressive and life-threatening genetic disease that produces very thick and sticky mucus. This mucus can clog and/or affect multiple organ systems but primarily affects the lungs and pancreas.

The leading theory is that for people with CF, ions and water do not move across the epithelium, the thin layer of tissue that lines all parts of the body. This makes it harder for tiny hair-like structures called cilia to wave around or ‘beat’, which would normally move mucus and the airborne bacteria it traps out of the lungs and airways.

When mucus clogs the airways of the lungs it can make breathing very difficult. It also provides a great breeding ground for bacteria that gets stuck in the airways and causes inflammation and serious, frequent, and sometimes life-threatening lung infections. When an individual with cystic fibrosis gets reoccurring lung infections, irreversible lung damage results.

The pancreas releases important enzymes that help us digest our food. These enzymes are not able to be released in CF patients because of the thick mucus. This makes it very hard to retain important nutrients and fats which in turn makes it very hard to gain and maintain weight. Supplemental enzymes are taken before each snack and meal to help in the digestive process.

People with CF have a variety of symptoms including: very salty-tasting skin; persistent coughing, at times with phlegm; wheezing or shortness of breath; an excessive appetite but poor weight gain; and greasy, bulky stools.

The disease has contributed much more to science than science has contributed to the disease. There is currently no cure for CF. In 2014, the US Food and Drug Administration declared Ivacaftor, the drug approved for CF sufferers, is showing promising results. Existing gene therapy trials in the UK are bringing people with the illness closer to a form of cure. Gene therapy is a way of treating or curing a disease by adding a copy of a healthy gene to do the job of a faulty one. Gene therapy is not a cure for cystic fibrosis, but effective gene therapy could halt or prevent the lung damage that causes 90 per cent of deaths. Gene therapy would benefit most people with cystic fibrosis and works regardless of age as it replaces the faulty gene mutation with a correct version. Although it cannot reverse lung damage, it would stop lungs from deteriorating further.